2. Open Research Data and Materials

What is it?

Open research data is data that can be freely accessed, reused, remixed and redistributed, for academic research and teaching purposes and beyond. Ideally, open data have no restrictions on reuse or redistribution, and are appropriately licensed as such. In exceptional cases, e.g. to protect the identity of human subjects, special or limited restrictions of access are set. Openly sharing data exposes it to inspection, forming the basis for research verification and reproducibility, and opens up a pathway to wider collaboration. At most, open data may be subject to the requirement to attribute and sharealike (see the Open Data Handbook).

Rationale

Research data are often the most valuable output of many research projects, they are used as primary sources that underpin scientific research and enable derivation of theoretical or applied findings. In order to make findings/studies replicable, or at least reproducible or reusable (see Reproducible Research And Data Analysis) in any other way, the best practice recommendation for research data is to be as open and FAIR as possible, while accounting for ethical, commercial and privacy constraints with sensitive data or proprietary data.

Learning objectives

Gain an understanding of the basic characteristics and principles of open and FAIR research data, including appropriate packaging and documentation, to enable others to understand, reproduce, and re-use in alternative ways.

Familiarity with the sorts of data that might be considered sensitive, and the restrictions or constraints on openly sharing them.

Be able to convert a ‘closed’ dataset into one which is ‘open’ by implementing the necessary measures in a data management plan, with appropriate data stewardship and metadata.

Be able to use research data management plan and to make your research results findable and accessible, even if it contains sensitive data.

Understand the pros and cons of openly sharing different types of data (e.g., privacy, sensitivity, de-identification, mediated access).

Understand the importance of appropriate metadata for sustainable archiving of research data.

Understand the basic workflows and tools for sharing research data.

Key components

Knowledge & Skills

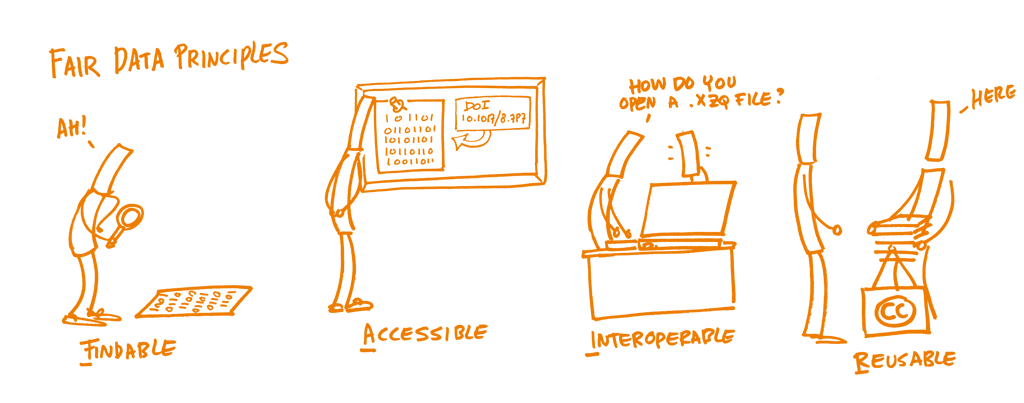

FAIR principles

In 2014, a core set of principles were drafted in order to optimize the reusability of research data, named the FAIR Data Principles. They represent a community-developed set of guidelines and best practices to ensure that data or any digital object are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Re-usable:

Findable: The first thing to be in place to make data reusable is the possibility to find them. It should be easy to find the data and the metadata for both humans and computers. Automatic and reliable discovery of datasets and services depends on machine-readable persistent identifiers (PIDs) and metadata.

Accessible: The (meta)data should be retrievable by their identifier using a standardized and open communications protocol, possibly including authentication and authorisation. Also, metadata should be available even when the data are no longer available.

Interoperable: The data should be able to be combined with and used with other data or tools. The format of the data should therefore be open and interpretable for various tools, including other data records. The concept of interoperability applies both at the data and metadata level. For instance, the (meta)data should use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles.

Re-usable: Ultimately, FAIR aims at optimizing the reuse of data. To achieve this, metadata and data should be well-described so that they can be replicated and/or combined in different settings. Also, the reuse of the (meta)data should be stated with (a) clear and accessible license(s).

Distinct from peer initiatives that focus on the human scholar, the FAIR principles put a specific emphasis on enhancing the ability of machines to automatically find and use data or any digital object, in addition to supporting its reuse by individuals. The FAIR principles are guiding principles, not standards. FAIR describes qualities or behaviours that are required to make data maximally reusable (e.g., description, citation). Those qualities can be achieved by different standards.

Data publishing

Most researchers are more or less familiar with Open Access publishing of research articles and books (see chapter 5). More recently, and for the reasons mentioned above, data publishing has gained increasing attention. More and more funders expect the data produced in research projects they finance to be findable, accessible and as open as possible.

There are several distinct ways to make research data accessible, including (Wikipedia):

Publishing data as supplemental material associated with a research article, typically with the data files hosted by the publisher of the article.

Hosting data on a publicly-available website, with files available for download.

Depositing data in a repository that has been developed to support data publication, e.g., Dataverse, Dryad), figshare, Zenodo.

A large number of general and domain or subject specific data repositories exist which can provide additional support to researchers when depositing their data.

Publishing a data paper about the dataset, which may be published as a preprint, in a journal, or in a data journal that is dedicated to supporting data papers. The data may be hosted by the journal or hosted separately in a data repository. Examples of data journals include Scientific Data (by SpringerNature) and the Data Science Journal (by CODATA). For a comprehensive review of data journals, see Candela et al.

The CESSDA ERIC Expert tour guide on Data Management provides an overview of pros and cons of different data publication routes. Sometimes, your funder or another external party requires you to use a specific repository. If you are free to choose, you may consider the order of preference in the recommendations by OpenAIRE:

Use an external data archive or repository already established for your research domain to preserve the data according to recognised standards in your discipline.

If available, use an institutional research data repository, or your research group’s established data management facilities.

Use a cost-free data repository such as Dataverse, Dryad, figshare or Zenodo.

Search for other data repositories in re3data. There is no single filter option in re3data covering the FAIR principles, but considering the following filter options will help you to find FAIR-compatible repositories: access categories, data usage licenses, trustworthy data repositories (with a certificate or explicitly adhering to archival standards) and whether a repository gives the data a persistent identifier (PID). Another aspect to consider is whether the repository supports versioning.

You should consider where to deposit and publish your data already in your research data management plan. CESSDA offers some practical questions, which are recommended to be considered. For example: Which data and associated metadata, documentation and code will be deposited? How long does the data need to be retained? For how long should the data remain reusable? How will the data be made available? What access category will you choose? For more questions check Adapt your DMP: part 6. On the other hand don’t forget to check if a chosen repository meets requirements of your research and of your funder. Some repositories have already gained certification, like CoreTrustSeal, which certifies them to be trustworthy and to be able to meet Core Trustworthy Data Repositories Requirements. It is worth mentioning that some domain specific repositories may accept only high-quality data with a potential for reuse and that can be publicly shared.

Since there are several routes to publish your data, you should note that for a dataset to "count" as a publication, it should follow a similar publication process as an article (Brase et al., 2009) and should be:

Properly documented with metadata;

Reviewed for quality, e.g. content of the study, methodology, relevance, legal consistency and documentation of materials;

Searchable and discoverable in catalogues (or databases);

Citable in articles.

Data citation

Data citation services help research communities discover, identify, and cite research data (and often other research objects) with confidence. This typically involves the creation and allocation of Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) and accompanying metadata through services such as DataCite, and can be integrated with research workflows and standards. This is an emerging field, and involves aspects such as conveying to journal publishers the importance of appropriate data citation in articles, as well as enabling research articles themselves to be linked to any underlying data. Through this, citable data become legitimate contributions to the process of scholarly communication, and can help pave the way for new metrics and publication models that recognize and reward data sharing.

As an initial step towards good practice for data citation, the Data Citation Synthesis Group of FORCE11 has put forward the Joint Declaration of Data Citation Principles, targeted at both researchers and data service providers. Adhering to these principles, data repositories usually provide researchers with a reference they can use when referring to a given dataset.

Data packaging

Data packages are containers for describing and sharing accompanying data files, and typically comprise a metadata file describing the features and context of a dataset. This can include aspects such as creation information, provenance, size, format type, field definitions, as well as any relevant contextual files, such as data creation scripts or textual documentation. From the Data Packaging Guide:

Data are forever: Datasets outlive their original purpose. Limitations of data may be obvious within their original context, such as a library catalog, but may not be evident once data is divorced from the application it was created for.

Data cannot stand alone: Information about the context and provenance of the data--how and why it was created, what real-world objects and concepts it represents, the constraints on values--is necessary to helping consumers interpret it responsibly.

Structuring metadata about datasets in a standard, machine-readable way encourages the promotion, shareability, and reuse of data.

Sharing sensitive and proprietary data

With appropriate data management planning much sensitive and proprietary data can be shared, reused, and FAIR. The metadata can almost always be shared. Guidance and best practices for sharing sensitive data are necessarily region-specific because of differing regulations (see for example UKDS’Companion material for Managing and Sharing Research Data handbook). International Association for Social Science Information Services and Technology keeps a list of international guidance in data management that is a good starting point. There are several approaches and initiatives to help researchers achieve this. DCC’s DMPonline tool includes a number of templates for funders. The CESSDA Expert Tour Guide on Data Management provides information and practical examples on how to share personal data and on copyright and database issues across the European countries. The Tour Guide also gives an overview on the impact of the GDPR which will harmonize personal data legislation in Europe (May 2018), and provides an updated overview on EU diversity on data protection.

Data brokers

Data brokers are knowledgeable, independent parties who act as data stewards for sensitive data. Researchers can transfer their sensitive data and jurisdiction over access to that data to the broker. This is especially common with patient-level data from clinical studies. Brokers provide a level of independence in the evaluation of whose data requests are scientifically valid and will not violate the privacy of research participants. Examples of data brokers include The YODA Project, ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com, National Sleep Research Resource and Supporting Open Access for Researchers (SOAR).

Analysis portals

Analysis portals are platforms that allow approved analysis of data without allowing full access (viewing or downloading) or controlling where and who gets access. Some data brokers also use analysis portals. Analysis portals control what additional datasets can be pooled with the sensitive data as well as what analyses can be run to ensure that personal information is not revealed during reanalysis. Examples of virtual analysis portals include Project Data Sphere, Vivli, RAIRD, Corpuscle, and INESS.

Social science and other researchers with sensitive data use a single-site analysis portal that can be accessed only under controlled regime. Approved researchers can access the data on-site, in a safe room, for scientific purposes. However, the metadata describing the data should be openly available and adhering to the FAIR principles.

De-identified and synthetic data

Many datasets containing participant-level private information can be shared once the dataset has been de-identified (Safe Harbor method) or a expert has determined that the dataset is not individually identifiable (Expert Determination method). Consult with your Research Ethics Board / Institutional Review Board to learn how to do this with your data. We also recommend the CESSDA Expert Tour Guide on Data Management, which provides information and practical examples on how to share personal data. However, some datasets cannot be safely de-identified and shared. Researchers can still improve the openness of research on such data by creating and sharing synthetic data. Synthetic data is similar in structure, content, and distribution to the real data and aims to attain "analytic validity": statistical analysis will return the same results for the synthetic data as the real data. The United States Census Bureau, for example, uses synthetic data and analysis portals in combination to allow reuse of highly sensitive data.

DataTags

DataTags is a framework designed to enable computer-assisted assessments of the legal, contractual, and policy restrictions that govern data sharing decisions. The DataTags system asks a user a series of questions to elicit the key properties of a given dataset and applies inference rules to determine which laws, contracts, and best practices are applicable. The output is a set of recommended DataTags, or simple, iconic labels that represent a human-readable and machine-actionable data policy, and a license agreement that is tailored to the individual dataset. The DataTags system is being designed to integrate with data repository software, and it will also operate as a standalone tool. DataTags is being developed at Harvard University. In Europe, DANS is working on adjusting DataTags to European legislation / General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (cf. DANS GDPR DataTags).

As mentioned above, the ultimate goal of data sharing your research data is to make them maximally reusable. To that end, before sharing your data you should manage them according to best practice. This includes, i.a., documentation and the choice of open file formats and licenses. You can read more about these issues in Section 4: Reproducible Research and Data Analysis as well as Section 6: Open Licensing and File Formats.

Open Materials

In addition to data sharing, the openness of research relies on sharing of materials. What materials researchers use is discipline-specific and sometimes unique to a lab. Below are examples of materials you can share, although always confer with peers in your discipline to identify which repositories are used. When you have materials, data, and publications from the same research project shared in different repositories, cross-reference them with a link and a unique identifier so they can be easily located.

Reagents

A reagents is a substance, compound or mixture that can be added to a system in order to create a chemical or other reaction. Reagents can be deposited with repositories like Addgene, The Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and ATCC to make them easily accessible to other researchers. License your materials so they can be reused by other researchers.

Protocols

A protocol describes a formal or official record of scientific experimental observations in a structured format. Deposit virtual protocols for citation, adaptation, and reuse using Protocols.io.

Notebooks, containers, software, and hardware

Reproducible analysis is aided by the use of literate programming, container technology, and virtualization. In addition to sharing your code and data, also share your Jupyter notebooks, Docker images, or other analysis materials or software dependencies. Share notebooks with Open services such as mybinder that allow for public viewing and execution of the entire notebook on shared resources. Containers and notebooks can be shared with Rocker or Code Ocean. Software and hardware used in your research should be shared following best practices for documentation as outlined in Section 3. Read-only protocols should be deposited in your disciplines registry such as ClinicalTrials.gov and SocialScienceRegistry or a general registry like Open Science Framework. Many journals, such as Trials, JMIR Research Protocols, or Bio-Protocol, will publish your protocol. Best practices for publishing your protocol open access are the same as publishing your report open access (see Section 5).

Questions, obstacles, and common misconceptions

Q: "Is it sufficient to make my data openly available?"

A: "No—openness is a necessary but not sufficient condition for maximum reuse. Data have to be FAIR in addition to open."

Q: "What do the FAIR principles mean/imply for different stakeholders/audiences?"

A: "This is a great topic for discussion!"

Obstacle: Researchers may be reluctant to share their data because they are afraid that others will reuse them before they have extracted the maximum usage from them, or that others might not fully understand the data and therefore mis-use them.

(suggested) A: You may publish your data to make them findable with metadata, but set an embargo period on the data to make sure that you can publish your own article(s) first.

Q: "Is making my data FAIR a lot of extra work?"

A: "Not necessarily! Making data FAIR is not only the responsibility of the individual researchers but of the whole group. The best way to ensure that your data is FAIR is to create a Data Management Plan and plan everything beforehand. During the data collection and data processing follow the discipline standards and measures recommended by a repository.

Q: "I want to share my data. How should I license them?"

A: "That’s a good question. First of all think about who owns the data? A research funder or an institution that you work for. Then, think about authorship. Applying a suitable license to your data is crucial in order to make them reusable. For more information about licensing, please see 6. Open Licensing and File Formats.

Q: "I cannot make my data directly available—they are too large to share conveniently / have restrictions related to privacy issues. What should I do?"

A: "You should talk to experts in domain specific repositories on how to provide sufficient instructions to make your data findable and accessible."

Learning outcomes

Understand the characteristics of open data, and in particular the FAIR principles.

Be familiar with some of the arguments for and against open data.

Be able to differentiate and address sensitive data and opFAIR data; these two categories are not necessarily incompatible.

Be able to transform a dataset into one that is sufficient for open sharing (non-proprietary format), meets the standards of the FAIR principles, and is designed for maximized accessibility, transparency and re-use by providing sufficient metadata.

Know the difference between raw and processed (or cleaned) data, and the importance of version labels.

Know commonly used file formats and community standards for maximum re-usability.

Be able to write a data management plan.

Further reading

Averkamp et al. (2018). Data packaging guide. github.com/saverkamp/beyond-open-data/blob/master/DataGuide.md.

Barend et al. (2017). Cloudy, increasingly FAIR; revisiting the FAIR Data guiding principles for the European Open Science Cloud. doi.org/10.3233/ISU-170824

Brase et al. (2009). Approach for a joint global registration agency for research data. doi.org/10.3233/ISU-2009-0595

Candela et al. (2015). Data journals: A survey. doi.org/10.1002/asi.23358

CESSDA Training Working Group (2017-2018a). CESSDA Data Management Expert Guide. Bergen, Norway: CESSDA ERIC. cessda.eu/DMGuide

CESSDA Training Working Group (2017-2018b). CESSDA Data Management Expert Guide: Citing your data. Bergen, Norway: CESSDA ERIC.cessda.eu/DMGuide/citingdata

FAIRsharing.org (2016). FAIR. The FAIR Principles. doi.org/10.25504/FAIRsharing.WWI10U

Force 11 (n.y.). Guiding principles for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Re-usable data publishing Version B1.0. force11.org/fairprinciples

Gorgolewski et al. (2013). Making data sharing count: a publication-based solution. doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00009

Kratz and Strasser (2015). Making Data Count. doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2015.39

Piwowar and Vision (2013). Data reuse and the open data citation advantage. doi.org/10.7717/peerj.175

Wilkinson et al. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

Wilkinson et al. (2918). A design framework and exemplar metrics for FAIRness. doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.118

Initiatives and projects

DANS GDPR DataTags. zingtree.com

FAIR Metrics. fairmetrics.org

GO FAIR Initiative. go-fair.org

The FAIR Data Principles explained. go-fair.org

5★ OPEN DATA. 5stardata.info