4. Reproducible Research and Data Analysis

What is it?

Reproducibility means that research data and code are made available so that others are able to reach the same results as are claimed in scientific outputs. Closely related is the concept of replicability, the act of repeating a scientific methodology to reach similar conclusions. These concepts are core elements of empirical research.

Improving reproducibility leads to increased rigour and quality of scientific outputs, and thus to greater trust in science. There has been a growing need and willingness to expose research workflows from initiation of a project and data collection right through to the interpretation and reporting of results. These developments have come with their own sets of challenges, including designing integrated research workflows that can be adopted by collaborators while maintaining high standards of integrity.

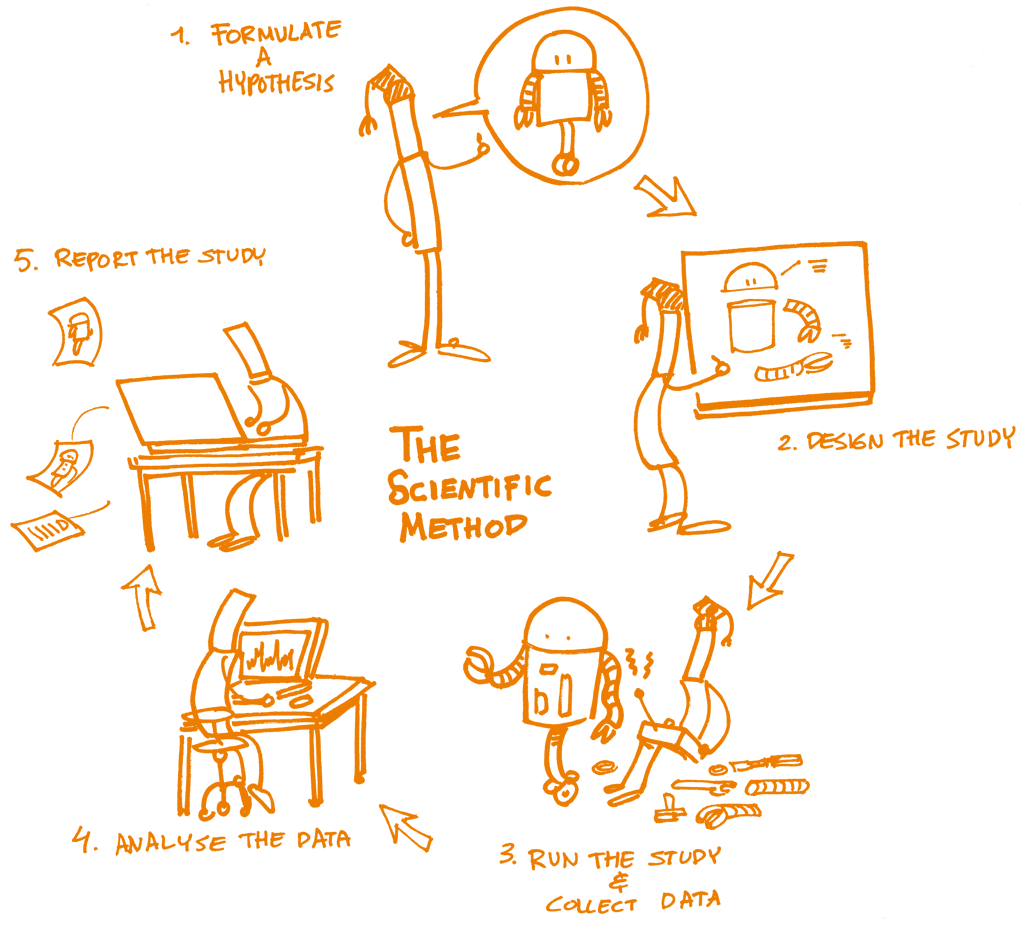

The concept of reproducibility is directly applied to the scientific method, the cornerstone of Science, and particularly to the following five steps:

Formulating a hypothesis

Designing the study

Running the study and collecting the data

Analyzing the data

Reporting the study

Each of these steps should be clearly reported by providing clear and open documentation, and thus making the study transparent and reproducible.

Rationale

Overarching factors can further contribute to the causes of non-reproducibility, but can also drive the implementation of specific measures to address these causes. The culture and environment in which research takes place is an important ‘top-down’ overarching factor. From a ‘bottom-up’ perspective, continuing education and training for researchers can raise awareness and disseminate good practice.

While understanding the full range of factors that contribute to reproducibility is important, it can also be hard to break down these factors into steps that can immediately be adopted into an existing research program and immediately improve its reproducibility. One of the first steps to take is to assess the current state of affairs, and to track improvement as steps are taken to increase reproducibility even more. Some of the common issues with research reproducibility are shown in the figure below.

Source: Symposium report, October 2015. Reproducibility and reliability of biomedical research: improving research practice PDF.

Goodman, Fanelli, & Ioannidis (2016) note that in epidemiology, computational biology, economics, and clinical trials, reproducibility is often defined as:

"the ability of a researcher to duplicate the results of a prior study using the same materials as were used by the original investigator. That is, a second researcher might use the same raw data to build the same analysis files and implement the same statistical analysis in an attempt to yield the same results."

This is distinct from replicability: "which refers to the ability of a researcher to duplicate the results of a prior study if the same procedures are followed but new data are collected." A simpler way of thinking about this might be that reproducibility is methods-oriented, whereas replicability is results-oriented.

Reproducibility can be assessed at several different levels: at the level of an individual project (e.g., a paper, an experiment, a method or a dataset), an individual researcher, a lab or research group, an institution, or even a research field. Slightly different kinds of criteria and points of assessment might apply to these different levels. For example, an institution upholds reproducibility practices if it institutes policies that reward researchers who conduct reproducible research. On the other hand, a research field might be considered to have a higher level of reproducibility if it develops community-maintained resources that promote and enable reproducible research practices, such as data repositories, or common data-sharing standards.

Learning objectives

There are three major objectives that need to be addressed here:

Understand the important impact of creating reproducible research.

Understand the overall setup of reproducible research (including workflow design, data management and dynamic reporting).

Be aware of the individual steps in the reproducibility process, as well as the corresponding resources that can be employed.

Key components

Knowledge

The following is an indicative list of take-away points on reproducibility:

What is the ‘reproducibility crisis’, and meta-analyses of reproducibility.

Principles of reproducibility, and integrity and ethics in research.

What are the computing options and environments that allow collaborative and reproducible set up.

Factors that affect reproducibility of research.

Data analysis documentation and open research workflows.

Reproducible analysis environments (virtualization).

Addressing the "Researcher Degrees of Freedom" (Wicherts et al., 2016).

Skills

There are several practical tips for reproducibility that one should have in mind when setting out the particular skills necessary to ensure this. Best practices in reproducibility borrow from Open Science practices more generally but their integration offers benefits to the individual researcher themselves, whether they choose to share their research or not. The reason that integrating reproducibility best practices benefits the individual researcher is that they improve the planning, organization, and documentation of research. Below we outline one example of implementing reproducibility into a research workflow with references to these practices in the handbook.

1. Plan for reproducibility before you start

Create a study plan or protocol.

Begin documentation at study inception by writing a study plan or protocol that includes your proposed study design and methods. Use a reporting guideline from the Equator Network if applicable. Track changes to your study plan or protocol using version control (reference to Version Control). Calculate the power or sample size needed and report this calculation in your protocol as underpowered studies are prone to irreproducibility.

Choose reproducible tools and materials

Select antibodies that work using an antibody search engine like CiteAb. Avoid irreproducibility through misidentified cell lines by choosing ones that are authenticated by the International Cell Line Authentication Committee. Whenever possible, choose software and hardware tools where you retain ownership of your research and can migrate your research out of the platform for reuse (see Open Research Software and Open Source).

Set-up a reproducible project

Centralize and organize your project management using an online platform, a central repository, or folder for all research files. You could use GitHub as a place to store project files together or manage everything using a electronic lab notebook such as Benchling, Labguru,or SciNote. Within your centralized project, follow best practices by separating your data from your code into different folders. Make your raw data read-only and keep separate from processed data (reference to Data Management).

When saving and backing up your research files, choose formats and informative file names that allow for reuse. File names should be both machine and human readable (reference to Data Management). In your analysis and software code, use relative paths. Avoid proprietary file formats and use open file formats (see 6 Open Licensing and File Formats).

2. Keep track of things

Registration

Preregister important study design and analysis information to increase transparency and counter publication bias of negative results. Free tools to help you make your first registration include AsPredicted, Open Science Framework, and Registered Reports. Clinical trials should use Clinicaltrials.gov.

Version control

Track changes to your files, especially your analysis code, using version control (see Open Research Software and Open Source).

Documentation

Document everything done by hand in a README file. Create a data dictionary (also known as a codebook) to describe important information about your data. For an easy introduction, use: Karl Broman’s Data Organization module and refer to Data Management.

Literate programming

Consider using Jupyter Notebooks, KnitR, Sweave, or other approaches to literate programming to integrate your code with your narrative and documentation.

3. Share and license your research

Data

Avoid supplementary files, decide on an acceptable permissive license, and share your data using a repository. Follow best practices as outlined in the Open Research Data and Materials chapter.

Materials

Share your materials so they can be reused. Deposit reagents with repositories like Addgene, The Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and ATCC to make them easily accessible to other researchers. For more information, see the Open Materials subsection of Open Research Data and Materials.

Software, notebooks, and containers

License your code to inform about how it may be (re)used. Share notebooks with services such as mybinder that allow for public viewing and execution of the entire notebook on shared resources. Share containers or notebooks with services such as Rocker or Code Ocean. Follow best practices outlined in Open Research Software and Open Source.

4. Report your research transparently

Report and publish your methods and interventions explicitly and transparently and fully to allow for replication. Guidelines from the Equator Network, tools like Protocols.io, or processes like Registered Reports can help you report reproducibly. Remember to post your results to your public registration platform (such as ClinicalTrials.gov or the SocialScienceRegistry) within a year of finishing your study no matter the nature or direction of your results.

Questions, obstacles, and common misconceptions

Q: "Everything is in the paper; anyone can reproduce this from there!"

A: This is one of the most common misconceptions. Even having an extremely detailed description of the methods and workflows employed to reach the final result will not be sufficient in most cases to reproduce it. This can be due to several aspects, including different computational environments, differences in the software versions, implicit biases that were not clearly stated, etc.

Q: "I don’t have the time to learn and establish a reproducible workflow."

A: In addition to a significant number of freely available online services that can be combined and facilitate the setting up of an entire workflow, spending the time and effort to put this together will increase both the scientific validity of the final results as well as minimize the time of re-running or extending it in further studies.

Q: "Terminologies describing reproducibility are challenging."

A: See Barba (2018) for a discussion on terminology describing reproducibility and replicability.

Learning outcomes

Understand the necessity of reproducible research and its reasoning.

Be able to establish a reproducible workflow within the context of an example task.

Know tools that can support reproducible research.

Further reading

Button et al. (2013). Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. doi.org/10.1038/nrn3475

Karl Broman (n.y.). Data Organization. Choose good names for things. kbroman.org